View Life on the Kaw: The Working Kaw in a larger map. Click here for help with our maps.

Humans have always used the Kansas River for sustenance, from the first Indians who fished and traveled by canoe along the river, to the industries that developed on its banks and poured their waste back into its waters, to the urban populations who depend on the river for drinking water today. Like all rivers, the Kaw is a hardworking stream that is often under-appreciated as a source of wealth and economic vitality.

Trading and Travel

Trading along the river started as far back as the 1700s. Long before Kansas was opened up for white settlement, Europeans came here in search of fortunes. One of the best known traders along the Kaw was Moses Grinter, who arrived in the 1820s, set up a ferry across the Kansas River and opened a trading post to trade with the Delaware Indians. He married a Delaware named Annie, and they built a brick house, which today is Grinter House Museum on the north side of the Kaw in Kansas City, Kansas. It is a state historic site maintained by the Kansas State Historical Society. Picture of Grinter House Museum on right is courtesy of Craig Thompson.

The Kaw was one of the first dangers travelers faced on the Oregon Trail. Most travelers left Independence, Missouri, on the five-month journey in spring so they could get to the other side of the mountains before winter. But in spring, the Kaw was treacherous; in those days before dams upstream controlled the flow, the Kaw could become a roiling, angry river. Most crossed at Pappan’s Ferry in what is now downtown Topeka. The Pappan brothers were married to Josette and Julie Gonville, sisters whose mother was a Kaw Indian. The Pappans’ ferry boat in 1843 consisted of three dugout canoes supporting a single deck, and they charged $1 per wagon to cross. By 1849, the brothers had two boats in operation, each able to carry two wagons. They lowered the wagons to the river with ropes and had a team of oxen on the other side to pull them out.

In 1849, a Missouri newspaper reported that when the Kaw River was high, travelers would find an excellent ford at Uniontown. Thousands of emigrants bypassed Pappan’s Ferry at Topeka and headed 15 miles west for this location, which became known as the Upper Kansas Crossing. The Kaw River crossing, eight days out of Independence, became the traditional place where wagon trains reorganized, tightened discipline, and elected leaders. At a given signal, men who wanted to lead the journey would march across the prairie, and the travelers would run behind the candidate of their choice. The man with the longest tail of people following him was thus elected. At least two ferries began operating near the ford in the Kaw at Uniontown, and each was said to carry 65 to 70 wagons per day. At $1 per wagon, the ferry operators made a handsome wage for the time.

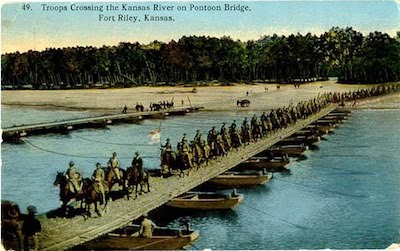

Although the Kaw ran high in spring, it was shallow and braided with sandbars most of the year. As a result, navigation was often a questionable proposition. When Fort Riley was established in 1853, The military sent several shipments up the river when the water was high, and many other steamboat operators arrived in hopes of trading upriver. Service was regularly offered from Kansas City to Lawrence and sometimes Topeka and even Fort Riley. All told, 34 steamboats are known to have plied the Kansas from 1854 to 1866, with cargoes of freight and passengers. The Lightfoot of Quindaro, said to be the first boat built in Kansas Territory, was specially built for the Kaw River, but it spent more than a month in 1857 making the round trip from Kansas City to Lawrence, most of the time stuck on sandbars, and was then shifted to operating on the Missouri River. The last steamer to travel the Kaw was the Alexander Majors, which was chartered in 1866 to run between Kansas City and Lawrence until the railroad bridge at the mouth of the river, which had been destroyed by floods, could be rebuilt.

Navigation was doomed by an act of the Kansas Legislature in 1864 declaring the Kaw non-navigable, a political move designed to help the railroads build bridges and dams. The law was repealed in 1913, and the Kaw was again declared navigable, but by then there was little demand for river travel.

Bowersock Dam

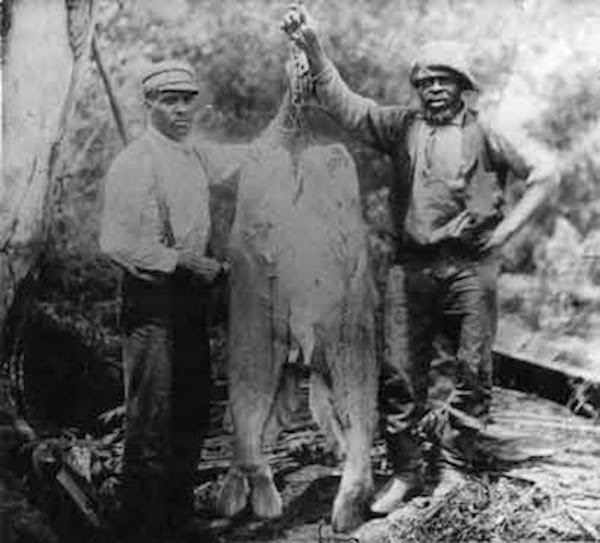

In 1876 the Bowersock family built a hydroelectric dam on the Kaw (pictured above) to provide power to the fledgling city of Lawrence, making it one of few cities in the West that had electricity in 1878 when Edison worked out the bugs in the incandescent light bulb and started the electric age. The Bowersock power plant (pictured on left) attracted a number of industries to Lawrence. Among those that thrived were four competing companies that set up manufacturing of barbed wire in 1878, shortly after it was invented. Lawrence quickly became the barbed wire capital of the West because transportation costs were much lower than from eastern manufacturing plants. The four competing companies eventually merged into one and were acquired by an east coast company, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel, that moved the business out of Lawrence in 1898.Other industries that located on the river to buy the power from Bowersock Dam included a paper mill, a flour mill, and a chemical manufacturer. Today, the Bowersock Dam still produces green power that is sold to the local utility company. It is the only dam on the main stem of the Kaw. The dam created a mill pond where catfish gathered, which resulted in a thriving commercial fishing business in Lawrence at the turn of the 20th century. The north side of the river was lined with little fishermen’s shacks and boat rental shops. Fishermen used conventional nets and trap lines from flat-bottomed boats, but they also engaged in a risky business called “noodling.” With a big hook tied to his wrist, a fisherman would dive to the bottom of the dam and feel around in the darkness for the big catfish that lived there. He physically hooked the fish, and dragged it to the surface. The entertainment center near the dam today called Abe and Jake’s Landing (pictured on right) is named in memory of Abe Burns and Jake Washington, two fishermen who had a cabin next to the barbed-wire building & pictured below. Jake died trying to bring up a catfish that was too big for him to handle.

local utility company. It is the only dam on the main stem of the Kaw. The dam created a mill pond where catfish gathered, which resulted in a thriving commercial fishing business in Lawrence at the turn of the 20th century. The north side of the river was lined with little fishermen’s shacks and boat rental shops. Fishermen used conventional nets and trap lines from flat-bottomed boats, but they also engaged in a risky business called “noodling.” With a big hook tied to his wrist, a fisherman would dive to the bottom of the dam and feel around in the darkness for the big catfish that lived there. He physically hooked the fish, and dragged it to the surface. The entertainment center near the dam today called Abe and Jake’s Landing (pictured on right) is named in memory of Abe Burns and Jake Washington, two fishermen who had a cabin next to the barbed-wire building & pictured below. Jake died trying to bring up a catfish that was too big for him to handle.

Back then, plenty of the fish were huge. Francis H. Snow, Kansas University’s chancellor at the turn of the 20th century and presumably a reliable witness, wrote in 1875 that he saw a blue catfish weighing 175 pounds and heard of a 250-pounder. Commercial fishing was eventually restricted, but many sport fishermen continue to catch big catfish in the Kaw.

Railroads

Railroads have played an important role in the settlement of Kansas. The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 gave almost 4 million acres of land to the Kansas Pacific Railroad, which built its main line from Kansas City, Missouri, to Denver, much of it right beside the Kaw River. The Kansas Pacific (KP), which later merged with the Union Pacific, aggressively promoted the sale and settlement of land along the river so that the railroad would have a population to serve (Union Pacific train crosses the Delaware River just before it enters the Kaw on left.) The KP published a quarterly newsletter that circulated to 80,000 people touting the beauty and bounty of western Kansas. “Good soil for wheat, corn and fruit,” trumpeted an early ad for settlers to southwest Kansas. At the time, a quasi-scientific theory held that “rain follows the plow.” People observed that in eastern Kansas, early settlers had quickly changed the empty prairie into verdant farmland. The theory was that when the prairie sod was plowed, the exposed soil could absorb more water, which would in turn foster evaporation and the formation of clouds, producing more rain and a more hospitable climate. The idea

attracted many supporters, including Ferdinand V. Hayden, director of the U.S. Geological and Geophysical Survey in the Territories. The railroads seized on the idea and promoted it throughout the East and in Europe. They offered free or reduced train fare to those who would settle in the West. Thousands did but, of course, the theory was nonsense, and when drought returned to the Plains in the 1870s, many settlers in both western and eastern Kansas gave up and moved back East. A Burlington Northern Santa Fe train runs along south side of Kaw, pictured on riget. Train pictures courtesy of Craig Thompson. Below paddlers explore a Kaw tributary under limestone rail road bridge.

Farming

The most important economic use of the land along the Kaw River is for farming: cropland comprises 60 percent of the floodplain and 28 percent of the 12-mile-wide Kaw Corridor, six miles on either side of the river. Today, the most important crops grown in the Kaw Valley are wheat, corn, soybeans, and milo. But in the past, vegetables and fruits were widely grown in the area. Historically, many Native American tribes, particularly women, grew vegetables in the fertile flood plain of the Kaw. By 1931, Kansas had been known as a fruit-producing state for more than sixty years. In 1871, Kansas apples won the highest award of the New Jersey Horticultural Society. In 1876, Kansas produce won a special medal at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, and Kansas grapes won heavily at the World’s Fair in Chicago.

Potatoes were the biggest crop, with 18,800 acres grown between Lecompton and De Soto in 1925. Farmers also grew sweet potatoes, beets, tomatoes, peas, beans, pumpkins, spinach, and sweet corn. Orchards and vineyards were abundant, too. Farmers’ menu of crops to take to grocery stores in Lawrence or to the City Market in Kansas City, Missouri, included apples, peaches, pears, and grapes. In 1900, a cannery opened in east Lawrence, giving Kaw Valley farmers a ready market for their vegetables. The Kaw Valley Cannery operated until 1925, when declining prices for canned goods shut it down. In 1930, Columbus Foods purchased and reopened the plant, and in 1950 Stokely-Van Camp bought it. The cannery continued producing canned vegetables into the 1980s, although by that time the produce was shipped in by rail.

Fruit and vegetable production in the Kaw Valley survived into the 1950s despite many challenges. Growing was never easy because of the unpredictable weather. Although eastern Kansas is an excellent place to grow horticultural crops, on average, extreme swings in the weather can ruin any given harvest. An abnormally bitter winter can kill trees, late spring freezes can ruin a budding fruit crop, and excessively hot, dry summers wreak havoc on vegetables. State apple harvest in 1919, for example, was 1.2 million bushels; two years later, orchards harvested only 100,000 bushels. The drought of 1934-1937 killed many orchards and vineyards in the valley, but farmers who survived replanted.

Even World War II and the extreme labor shortage it caused didn’t destroy the labor-intensive truck farming here. Local farm and business leaders worked with the Army to set up a prisoner-of-war camp just outside of Lawrence, and as many as 320 German POWs were moved here to work on farms, in businesses, and in construction. In July 1945, 175 prisoners of war harvested 1,000 acres of potatoes in this valley for 33 farmers. The flood of 1951 was the death knell for fruit and vegetable production, however. The Kaw and Wakarusa rivers raged out of their banks and covered virtually all of the floodplain. Orchards died, pea-shelling barns and equipment washed away, and soil was unworkable. As farmers recovered from the flood, many decided to try what was then a relatively new crop in the United States, soybeans. Bigger tractors introduced in the 1950s made larger-scale farming more practical, too, and farmers found they could make more money working with a tractor than doing the backbreaking physical work of vegetable farming.

In the past decade, though, vegetable farming has experienced a renaissance as small-scale farmers produce for local farmers’ markets,

restaurants, and Community Supported Agriculture programs. Farmers’ markets in particular are thriving in communities along the Kansas River. For information on places and times of Kansas farmers’ markets, click here.

Wyandotte County is home to the National Agricultural Center and Hall of Fame, which was chartered by Congress to honor America’s farmers. Inside the museum, extensive exhibits explain farming and rural life, with a large collection of machinery and implements of all vintages. Outside is a reconstructed 1900-era town, which includes a one-room school house, country store, veterinarian’s office, and other period buildings (pictured on right.) You can take a ride on a narrow-gauge railroad and tour an 1887 train depot. A brochure describes special events; the Agricultural Center has a number of celebrations which involve children, such as the Prairie Winds Kite Festival and Ice Cream Days. The center also offers educational programs for classes and groups that can be scheduled in advance.