The Friends of the Kaw has a special relationship with the great symbol of our river, the Bald Eagle. Our float trips are often graced with their presence, and their recovery from near extinction gives hope to all of us that the health of our river is within our control.

Bald Eagles are unique to North America, and are found nowhere else in the world. We think of them when we think of the Kaw because the river is their home– they build their nests in trees that line its banks, they fish in open water below Bowersock Dam during the winter, and they hunt ducks and geese on sandbars and wetlands all up and down the Kaw.

With a wing span over six feet, Bald Eagles are second only to the California Condor as the largest birds of prey in North America. When you see a pair of Bald Eagles at their nest, the bigger bird is the female– she will be about 25% larger than her mate. And their nests are the biggest of any other bird in the world (they have even made the Guinness Book of World Records!) A pair will usually mate for life, beginning at around 5 years old and living up to 30 years in the wild. Year after year they will work on their nest (also called an aerie), adding to it until it can weigh literally a ton.

You will see pairs of Bald Eagles working on their nests in the big trees along the Kaw all year round. According the Dan Mulhern, USFWS, the majority of eggs are laid in February in Kansas. Females can lay from 1 to 3 eggs, although 2 is the typical clutch. It takes a little over a month for them to hatch, after which you can see parents bring food to their chicks for another month. The most common food will be fish, which parents carefully tear up and feed to their young. After the chicks fledge they will still be seen returning to the nest for a few weeks to be fed by their parents as they learn to fly and forage for themselves.

The first successful nest on the Kansas River was seen in 1997. In the years from 1997 to 2010 there have been 12 nesting territories on the Kaw which produced a total of 122 fledged eaglets.

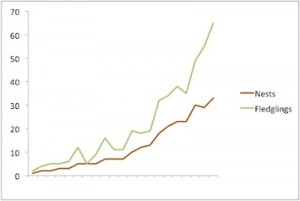

The number of nests in the state of Kansas has been steadily increasing from a single nest in 1989 to 33 nests in 2009 (see graph below). This means that the number of chicks that have fledged in Kansas has also been increasing. Only 2 chicks fledged in 1989, climbing to 65 in 2009.

In 2009 the pair built a new nest nearby and are still fishing on the river. Changing nesting locations is fairly common in Bald Eagles. When you visit the Lawrence 8th Street boat ramp make sure you keep an eye out for them. Young Bald Eagles have brown heads and tails, making them easy to confuse with Golden Eagles; their heads and tails turn white when they are 4-5 years old and ready to breed. This juvenile plumage serves a useful function because it tells adults that they are still youngsters and pose no threat to breeding territorial adults who may otherwise mistake them for competitors for nesting territories.

In addition to our resident breeding pairs, many more Bald Eagles migrate to Kansas in the winter when rivers and lakes in the northern parts of their range freeze over. Up to 3,000 Bald Eagles come to Kansas for the winter, arriving in early November and departing in mid to late March to return to their northern breeding grounds. During the Kansas winter they are drawn to places where the water remains open and they can go fishing. We like to celebrate our northern visitors every January with Eagle Day events in Lawrence and other towns around the state.

For more information click here to go to Bald Eagles in Kansas, brochure by Michael Watkins, Army Corps of Engineers

The species has been removed from both the Federal and State lists of endangered and threatened species, but is still protected by the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act as well as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. As such, it is a violation to “take” an individual, which can also result from disturbance such that a nesting attempt is not successful. No active nest should be approached any closer than 100 yards on foot or in a boat until and unless the pair exhibits an acceptance of such behavior. It may be possible to approach closer in a vehicle, but again, the behavior of the birds is critical. If you are causing an adult to flush from a nest, even temporarily, you are too close. If floating the river in a boat or canoe, it may not be possible to avoid a riverbank nest by this much distance. In this case, simply pass by as quietly and unobtrusively as possible if there is evidence of birds on the nest. (Guidelines for avoiding disturbance of Bald Eagles)

Thank you!

- To Dan Mulhern, USFWS and Mike Watkins, COE for information and assistance.

- Funding was provided by the Elizabeth Schultz Environmental Fund.

- Photos Michael A. Watkins Wildlife Biologist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

- Video courtesy of Mike Cuenca.

- Data on nesting and fledging rates from Great Plains Nature Center.

- Bald Eagles in Kansas Brochure courtesy of Michael A. Watkins, Army Corps of Engineers.

For more information:

- Status of Bald Eagles in Kansas, Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks.

- USFWS Fact Sheet

- Bald Eagles, All About Birds, Cornell Ornithology Lab.

- The Bald Eagle species account: Buehler, David A. 2000. Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/506doi:10.2173/bna.506